North Phoenix Water Shortage ‘Appears to be Inevitable’: City May Raise Rates

North Phoenix’s primary water supply from the Colorado River faces a better than 50/50 chance of a shortage in two years, and growing odds of what the city’s water chief calls “alarming” shortages in four years if Lake Mead were to fall below a “deadpool” level where water could no longer be provided to customers downstream. To prepare, Phoenix is considering raising water rates and spending $500 million to build pump stations and other infrastructure that would bring the precious commodity up the I-17 corridor from the city’s other water sources.

Phoenix’s water advisory committee recently recommended raising rates 6 percent in 2019 and another 6 percent in 2020 to fund the project, along with $1 billion for general rehabilitation of the city’s aging water infrastructure. The average Phoenix resident currently pays $33.62 per month for water.

City Council is expected to vote Oct. 9 on a “notice of intent” to approve the proposal, with a final vote planned for December after seeking public input. [Update: City Council voted in favor of the ‘notice of intent’ at it’s Oct. 9 meeting.]

“Right now, we are preparing for shortages and the worst-case scenario because any level of uncertainty is not acceptable,” said Thelda Williams, interim mayor and councilwoman for the city’s District 1.

The Problem

North Phoenix water comes from the Central Arizona Project (CAP). It originates in Rocky Mountain rainfall and snowmelt, and flows down the Colorado River and through a series of lakes—including Powell and Mead—and canals that lead to the Lake Pleasant Water Treatment Plant on New River Road just north of State Route 74 (Carefree Highway).

Phoenix and other municipal, farming and tribal customers throughout the West have rights to the Colorado River water dating back to “Law of the River” agreements that originated in the 1920s, during a historically wet period in the watershed. Given a return to more modest flows, followed by drought that has persisted the past 18 years, scientists and politicians now agree there is no longer enough water in the Colorado to meet the demand, should all parties request their full allotments.

Water officials throughout the West, including at CAP and in Phoenix, expect the situation to get worse.

Phoenix also gets water from the Salt and Verde rivers, but that water cannot be physically moved to North Phoenix given the current infrastructure, the city says.

Meanwhile, aquifers in the Phoenix Active Management Area contain extensive groundwater, including that which has been injected underground during good years, in a process called recharging. Some 6.8 million acre-feet of water have been recharged into the aquifer over time, adding to a naturally occurring quantity that is “many times greater,” said Doug MacEachern, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

The city uses about 300,000 acre-feet per year.

How much of the groundwater the City of Phoenix has rights to is a difficult question to answer, involving various agreements between municipalities and agencies and storage credits issued to them. But the city is optimistic.

“Phoenix has long been proactive by implementing smart water policies that have allowed us to store water for times of prolonged drought or extreme shortage—and we’ve been successful in banking water,” Williams told In&Out.

But the city doesn’t have enough wells to adequately tap the aquifers, and the bulk of the water is at elevations below the North Valley.

Worry of ‘Deadpool’

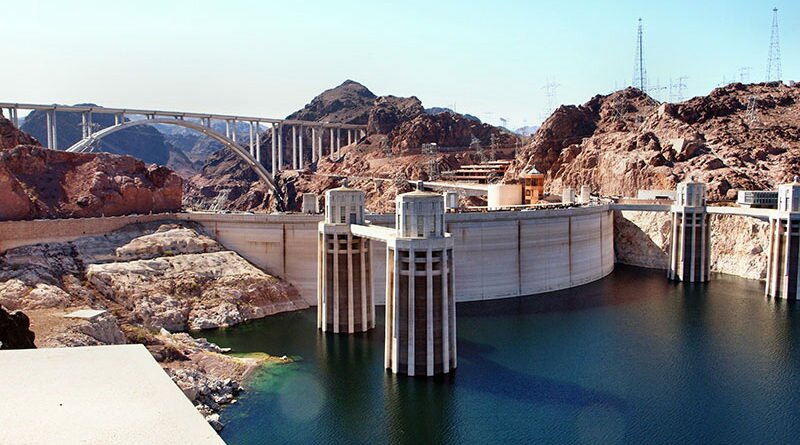

Already, more water is pulled out of the Colorado River system than flows in. The water level in Lake Mead, the country’s largest reservoir, has been falling for several years. Last month, the water’s surface elevation at the lake’s Hoover Dam was 1,079 feet. If it falls below 1,075 feet, it would trigger automatic cuts to downstream customers.

The first trigger would not impact municipal water supplies for CAP users, “but it would halt water deliveries for recharge,” CAP says. But further triggers and restrictions would result in a political football over so-called “guaranteed water rights,” pitting cities against farmers and states against states in a battle whose outcome is anyone’s guess, experts agree.

The Bureau of Reclamation cites a 57-percent chance of a first-trigger shortage in 2020.

“Because the Colorado River is over-allocated, and because snowpack has not been our friend, shortage appears to be inevitable,” said Kathryn Sorensen, director of Phoenix’s Water Services Department. And because the lake is V-shaped, the elevation drop may accelerate with each step down. If the lake falls below 1,025 feet, “the Law of the River is unclear and we enter unchartered territory,” Sorensen said.

“Most alarmingly, the Bureau of Reclamation recently produced a chart that shows Lake Mead could hit 985 feet in elevation within four years,” Sorensen said. “Elevation 985 feet constitutes deadpool in Lake Mead.” Below this level, water cannot physically enter the intakes that release water from the lake.

“The uncertainty that could result from extreme Colorado River shortages has the potential to hamper economic opportunity in our region and impact home values,” Sorensen told In&Out. She added, though, that if the city manages its “basket of supplies,” including groundwater and water from the Salt and Verde rivers, “we can meet demands, even in worst-case scenarios on the Colorado River, for decades,” so long as new infrastructure is built.

Phoenix Water by the Numbers

430,000 Metering devices

155,000 Valves

7,000 Miles of water mains

107 Pump stations

22 Active wells

8 Water treatment plants

The Solution

The idea is to spend $300 million on pipes and pump stations to move water into the city’s northern reaches by 2023. A $110-million project to drill 15 new wells by 2022 to extract groundwater is already underway, according to a city water, infrastructure and sustainability report. And the city is spending $75 million over the next five years on recharging aquifers and other “resiliency efforts.”

If the measure passes, rates for the average customer would increase to about $35.97 per month next year (a 6 percent increase). City officials point to 15 other large cities with higher monthly water rates: from $40.15 in Detroit to $131.20 in San Francisco.

(Anthem residents west of I-17 get Phoenix water. Anthem’s east side, which is not in Phoenix, is served by EPCOR, which also relies on CAP water. EPCOR rates are higher: $50.91 per month for the average customer, and expected to increase once a proposed rate hike is approved by the Arizona Corporation Commission. New River and Desert Hills residents rely on private wells or trucked-in water.)

While neither Williams nor Sorensen would lay odds on the measure’s passage, they made clear the funds are vital.

“If no rate hike is approved, Phoenix Water will need to cut its capital improvement plan drastically, and likely not be able to move forward with the infrastructure necessary to protect against extreme shortages on the Colorado River,” Sorensen said.

“I hope we will have strong support from the City Council,” Williams said. “I want to make sure we have an ample supply of water citywide.”

Open House: 5–6:30 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 8

Phoenix residents are invited to an open house to learn more about the planned increase.

Desert Broom Library

29710 N. Cave Creek Road, Cave Creek

Info: 602-262-4636